First, he thought it was a mouse, then a rat—and then the rat shot him in the face. That is how André Brink, one of South Africa’s most famous novelists, described the recent killing of his nephew Adri, at home at 3am in the morning. The young man was left to die on the floor,

First, he thought it was a mouse, then a rat—and then the rat shot him in the face. That is how André Brink, one of South Africa’s most famous novelists, described the recent killing of his nephew Adri, at home at 3am in the morning. The young man was left to die on the floor, in front of his wife and daughter, while his killers ransacked the house.

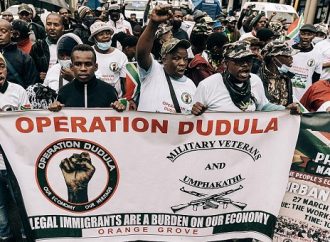

White flight from South Africa.

Such murders are common in South Africa. According to Mr Brink’s account, published later in the Sunday Independent, 16 armed attacks had already taken place in a single month within a kilometre of the young couple’s plot north of Pretoria, South Africa’s capital. Soon afterwards—this is more unusual—the police arrested a gang of six. They recovered a laptop and two mobile phones.

That was the haul for which Adri paid with his life. A decade-and-a-half after the end of apartheid, violent crime is pushing more and more whites out of South Africa. Exactly how many are leaving is impossible to say. Few admit that they are quitting for good, and the government does not collect the necessary statistics.

But large white South African diasporas, both English- and Afrikaans-speaking, have sprouted in Britain, Australia, New Zealand and many cities of North America.

The South African Institute of Race Relations, a think-tank, guesses that 800,000 or more whites have emigrated since 1995, out of the 4m-plus who were there when apartheid formally ended the year before.

Robert Crawford, a research fellow at King’s College in London, reckons that around 550,000 South Africans live in Britain alone. Not all of South Africa’s émigrés are white: skilled blacks from South Africa can be found in jobs and places as various as banking in New York and nursing in the Persian Gulf.

But most are white—and thanks to the legacy of apartheid the remaining whites, though only about 9% of the population, are still South Africa’s richest and best-trained people.

Talk about “white flight” does not go down well. Officials are quick to claim that there is nothing white about it. A recent survey by FutureFact, a polling organization, found that the desire to emigrate is pretty even across races: last year, 42% of Coloured (mixed-race) South Africans, 38% of blacks and 30% of those of Indian descent were thinking of leaving, compared with 41% of whites.

This is a big leap from 2000, when the numbers were 12%, 18%, 26% and 22% respectively. But it is the whites, by and large, who have the money, skills, contacts and sometimes passports they need to start a life outside—and who leave the bigger skills and tax gap behind.

Another line loyalists take is that South Africa is no different from elsewhere: in a global economy, skills are portable. “One benefit of our new democracy is that we are well integrated in the community of nations, so now more opportunities are accessible to our people,” Kgalema Motlanthe, now South Africa’s president, told The Economist.

And to some extent it is true that the doctors, dentists, nurses, accountants and engineers who leave are being pulled by bigger salaries, not pushed by despair. But this is not the whole story. Nick Holland, chief executive of Gold Fields, a mining company, says that in his firm it is far commoner for skilled whites to leave than their black and Indian counterparts. “We mustn’t stick our heads in the sand,” he says. “White flight is a reality.”

Another claim is that a lot of leavers return. Martine Schaffer, a Durbanite who returned to South Africa herself in 2003 after 14 years in London, now runs the “Homecoming Revolution”, an outfit created with help from the First

National Bank to tempt lost sheep back to the fold. And, yes, a significant number of émigrés do come home, seduced by memories of the easeful poolside life under the jacaranda trees, excited by work opportunities or keen—perhaps after having children themselves—to reunite with parents who stayed behind.

In some cases, idealism remains a draw. Whites who left in previous decades because they were repelled by apartheid, or who expected apartheid to end in a bloodbath, can find much to admire.

Whites build tall walls around their houses and pay guards to patrol their neighborhoods; they consider some downtown areas too dangerous to visit. But on university campuses and in the bright suburban shopping malls it is still thrilling to see blacks and whites mingling in a relaxed way that was unimaginable under apartheid.

Reasons not to panic?

So South Africa certainly has its white boosters. Michael Katz, chairman of Edward Nathan Sonnenbergs, a law firm in Johannesburg, hands over a book with the title “Don’t Panic!”, a collection of heartwarming reflections by disparate South Africans on why there is, even now, no better place than home.

Mr Katz ticks off the pluses as he sees them: minimal racial tension (a third of his own firm’s 350 professionals are black); a model constitution that entrenches the separation of powers and is “revered” by the people; a free press and free judiciary; a healthy

Parliament; a vibrant civil society; good infrastructure and a banking system untouched by the global credit crunch. The “one major negative” Mr Katz concedes is violent crime. If only this could be brought under control, he says, the

leavers would return.

But would they? Violent crime is undoubtedly the biggest single driver of emigration, the one factor cited by all races and across all professions when people are asked why they want to go. Police figures put the murder rate in 2007-08 at more than 38 per 100,000 and rape at more than 75 per 100,000.

This marks a big fall over the past several years, but is still astronomical by international standards (the murder rate was 5.6 per 100,000 in the United States last year). It has reached the point where most people say they have either been victims of violent crime themselves or know friends or relatives who have been victims. Typically, it is a break-in, carjacking, robbery or murder close to home that clinches a family’s long mulled-over decision to leave.

All the same, crime is far from being the only cause of white disenchantment. Some say that 2008 brought a “perfect storm”. A sequence of political and economic blows this year have buffeted people’s hope. Added together they provide reason to doubt whether the virtues ticked off by the exuberant Mr Katz—a model constitution, separation of powers, good infrastructure and so on—are quite so solid.

Good infrastructure? At the beginning of the year South Africa’s lights started to go out, plunging the thrumming shopping malls and luxury homes into darkness and stopping work in the gold and diamond mines.

This entirely avoidable calamity was caused by a distracting debate about the role of the private sector in electricity supply. Eskom, the state-owned utility in which many experienced white managers had been too quickly pushed aside, is now investing again in new plant under a new chairman, Bobby Godsell, a veteran mining executive. But for the time being power will remain in short supply and rationing and blackouts will continue.

As for that model constitution and the separation of powers, Desmond Tutu, the retired Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, was moved this week to describe the sordid battle between Jacob Zuma, Thabo Mbeki, the party, government, prosecuting authority and courts as suggestive of a “banana republic”. As well as being appalled by events at home this past year, whites have watched Robert Mugabe’s pauperisation of neighbouring Zimbabwe and wonder whether South Africa will be next to descend into the same spiral.

Besides, fear of crime cannot be separated from the other factors that make South Africans consider emigration. People who do not feel safe in their homes lose their faith in government.

John Perlman, who worked for the SABC, the state broadcaster, before resigning in a quarrel over political interference, does not believe that most people leave because they are afraid. “I think they leave when they lose heart,” he says. One white entrepreneur about to leave for New York says that it was not being held up twice at gunpoint that upset him most: it was the lack of interest the police showed afterwards.

Tony Leon, the former leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance, claims that policing has been devastated by cronyism and that the entire criminal-justice system is dysfunctional. The head of the police, Jackie Selebi, is on leave pending a corruption investigation.

How much does the outward flow of whites matter? South Africa can ill afford the loss of its best-trained people. Iraj Abedian, an economist and chief executive of Pan-African Capital Holdings, says a pitiful shortage of skills is one of the main constraints on economic growth.

He concedes that the ANC has pushed hard to give every eligible child a place in school, but argues that a “politically correct” focus on expanding access has come at the expense of quality. With virtually no state schools providing adequate teaching in science or maths, he says, the country has added to its vast problem of unemployment (every other 18-24-year-old is out of work) a no less vast problem of unemployability.

The gap they leave behind

On Mr Abedian’s reckoning, about half a million posts are vacant in government service alone because too few South Africans have the skills these jobs demand. Not a single department, he says, has its full complement of professionals. Local municipalities and public hospitals are also desperately short of trained people.

Dentists are “as scarce as chicken’s teeth” and young doctors demoralised by the low standards of hospital administration. Last May Azar Jammine, an independent economist, told a Johannesburg conference on the growing skills shortage that more than 25,000 teachers were leaving the profession every year and only 7,000 entering.

A blinkered immigration policy makes things worse. Nobody has a clue how many millions of unskilled Africans cross into South Africa illegally. But skilled job applicants who try to come in legally are obstructed by a barricade of regulations. Mr Abedian says that the ANC used to think that relying on foreigners would discourage local institutions from training their own people.

Now at least the government earmarks sectors where skills are in short supply and for which immigration procedures are supposed to be eased. In April, however, an internal report by the Department of Home Affairs showed that fewer than 1,200 foreigners had obtained permits under this scheme, from a list of more than 35,000 critical jobs.

In fairness, South Africa has been through far worse times before. Whites streamed out during the township riots of the 1980s. It is far from clear how much of the present dinner-table talk about leaving ends with a family packing its bags. Alan Seccombe, a tax expert at PWC in Johannesburg, says that many affluent whites have moved money offshore and prepared their escape routes, but that his firm’s emigration practice is doing less business today than it did in 1995.

Perspective is necessary in politics, too. Raenette Taljaard, previously an opposition member of Parliament and now director of the Helen Suzman Foundation, a think-tank, says that events this past year have raised profound concerns about the rule of law and the durability of the constitution.

But Allister Sparks, the author of several histories of South Africa (and a former writer for The Economist), maintains that the ANC has done as well as anyone had a right to expect after apartheid’s destructive legacy. Some whites even express enthusiasm about the advent of Mr Zuma. How many other African liberation movements, they ask, have been democratic enough to vote out an underperforming leader, as the ANC has Mr Mbeki?

For the average white person, South Africa continues to offer a quality of life hard to find elsewhere. And there are other compensations. Mr Brink says in the article on the murder of his nephew that people who ask when he will be emigrating are perplexed to hear that he intends to stay.

There is, he says, an “urgency and immediacy” about life in South Africa that lends it a sense of involvement and relevance he cannot imagine finding elsewhere.

All the same, he is staying on bereft of some former illusions.

The myopia and greed of the country’s new regime of rats have eroded my faith in the specific future I had once believed in. I do not foresee, today, any significant decrease in crime and violence in South Africa; I have serious doubts that our rulers can even guarantee a safe and successful soccer World Cup in 2010; I do not believe that the levels of corruption and nepotism and racketeering and incompetence and injustice and unacceptable practices of “affirmative action” in the country will decrease in the near future.

The famous novelist will stay. Many other whites are making plans to leave, and will be taking their precious skills with them.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *